Winter leaves a landscape sometimes snow covered with skeleton trees and frozen waters. Many find winter dampening, depressing, and void of beauty. I however, feel otherwise. My second stint in search of wintering raptors was full of breathtaking scenery and striking beauty. The desert aesthetic is an acquired taste for some. I myself have always been drawn to the subtle beauty of the sage steppe. After this past week, I have a renewed value for winter in the high desert. Sunset casts a warm glow across the cerulean lands, creating a calm comfort for all that feel. The juxtaposition of the warm glow of the setting sun against the harshness of the winter world and the impeding night is a wonder of the natural world. Balance is ever present, and even the wild creatures know enough to take advantage of the simple pleasures in life.

I came upon the Short-eared Owl atop the wheel line, watching the sun fall into the western skyline, seemingly dazed and content with the time at hand. In retrospect, this scene speaks to me in many ways. Perhaps the wild ones feel the importance of taking advantage of the simple pleasures of life, and slowing down to enjoy when times are good. No doubt that due to the way the owl reacted to my presence, it had recently finished a meal and needed nothing but to enjoy the warmth of the sun before the frigid frosts of night.

Colors are not vibrant or particularly potent in the high desert, but they are of course present and play a dramatic role in creating the world that I love. Taking in the expansive valleys surrounded by large goliath stone mountains creates a sense of mortality, deep time, and insignificance of individual life. These feelings coupled with the spectacular images provided by the sunlight and its play on snow filled clouds moving high above the valleys provides a sensational experience. I often found myself in deep thought and feeling as I reflected upon the wonders of the Great Basin.

The beautiful but simple colors of the desert provide the perfect backdrop for the many creatures that accent the scene. Many gregarious species travel the sage and rabbitbrush in search of food. The Juniper Titmouse is perhaps a favorite, and the sage landscape’s Bushtit, but of the many sparrows and larks, bluebirds, even buntings, the lone Loggerhead shrike is a favorite. The way the bird travels and hunts is delighting. Perched atop a shrub, the shrike steadies, surveying for prey. The bird’s flight is full of swoops, and charms the eye with the contrasting black, grey, and flashing white. In winter, the Loggerhead is joined by a relative, the Northern Shrike. I was lucky to find this relative and recognize what separated it from the Loggerhead. I was, however, unlucky in capturing an acceptable photograph of the bird to contrast it against the Loggerhead.

Raptors were everywhere to be seen. From the farmlands into the desert, the birds occupied every niche. Each time I came upon a bird, I did my best with identification, to glean information the best possible particular, and photograph with every opportunity. A bird that was more present than the previous November stint was the Rough-legged Hawk of the great north. With every Rough-legged I practiced my identification, strengthening my skills and enhancing my experience with the birds.

Identifying Hawks In Flight

As the Rough-legged Hawk was more present this month, I took the opportunity to hone my identification skills down to the particulars. In flight sexing, if possible, is very difficult. With some raptors, even ageing becomes nearly impossible. With the help of the camera, I was able to make take my impressions and assumptions, review the photos, correct my mistakes, and cross reference my field guides for the most precise analysis I could muster. This approach is what I call in depth field study.

The above photos are examples of what I would so often see as I watched a bird through my binoculars. I was able to tell almost instantly the species, but narrowing my ID any further became a challenge. The bird above flew through the area quickly so an in flight ID of sex and age was not possible. After reviewing the photos I found that due to the mottled under-wing lining, obvious dark bib, and dark trailing edge to the wing, this bird is most likely an adult male. There are pitfalls to some of these criteria, but I feel fairly confident in this ID.

While photographing a Horned Lark in a high desert valley on my last survey day, I noticed a large shape growing larger in the sky. Looking up, I saw the familiar flight of another Rough-legged wandering north, perhaps in search of food. The bird flew directly overhead, giving me a great opportunity to photograph and observe at close range. The excitement kept me from making any ID on sex or age, but again I went back to the photo to see what I could tell about the hawk. The most notable feature is the nearly black belly band of the bird. This coupled with the pale wing edge and tail band indicates that the bird is a juvenile. Also, there is a faint hint of paleness to the primaries, which supports the juvenile conclusion. Still, the mottled under-wing coverts and heavily marked breast make me wonder if this could be a male. So far in my study, nothing has told that it is possible to sex a juvenile. Perhaps this particular could be basis for future research.

The Ferruginous Hawk seemed to be more present this month as well. I saw many more birds in the farmlands and desert alike. The strikingly rich colors and contrast of the Ferruginous Hawk give the bird an heir of royalty. Its fierce gaze exemplifies this royalty as well. No wonder the bird was given the epithet regalis, for its regality is unquestionable.

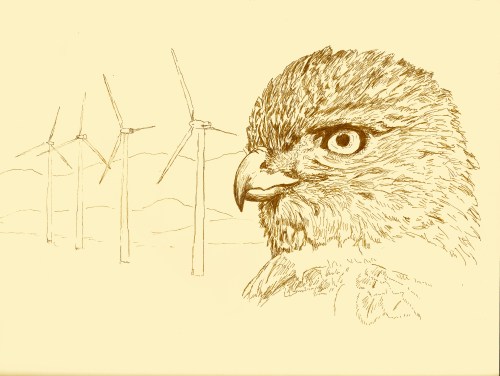

While surveying an area only miles from the Milford wind farm, I saw a large hawk flying across the horizon. After a quick glance through my field glasses, I knew the bird to be a Ferruginous Hawk. With a silver head and nape, rusty red coverts, pale primaries, and prime white tail, the large Buteo could be nothing else. I have since researched how to tell the difference between an adult and immature Ferruginous, and I believe the bird below is a typical adult light morph bird.

Given the rufous upper-wing and underwing coverts, rufous leggings, and the white tail lacking a terminal band, I feel fairly confident in my analysis. As with all buteos, when the varying color morphs are introduced, it can complicate things. The Ferruginous hawks I saw were all light morphs, save one. Atop a power pole only half a kilometer from the town of Minersville, I found a large dark bird watching a field for prey. I was unable to get a decent photo, but the picture below will have to do. I cannot help but share the bird.

Given the lack of a terminal tail band, I believe this bird to be an adult. There is a dark trailing edge to the remiges, but due to my mediocre camera skills, I chopped the wing in any other flight photos I took. I plan to go back to the area on my third stint to find this bird again and make another attempt to photograph it. One particularly neat aspect to this bird, and you can see clearly in this photo, is that the belly is a bit paler than the rest of the birds body. Dark morph buteos, especially in lagopus, seem to retain their plumage patterns. This makes sense as the dark plumage results from an increase in melanin in the feathers. In the case of this Ferruginous, the increase seems to be in phaeomelanin, responsible for rufous tones, and the areas where the rufous already exist seem darker than the areas that are regularly pale.

I could not believe the number of birds that occupied the areas that I travelled. Without question, the most incredible experience of the second survey stint was seeing the Short-eared Owl atop the wheel line, glowing golden from the falling sun. Content for the time being, the bird watched the warm rays as they caught fire against the frozen valley. As I watched the dazed and docile bird, I realized that for the moment, the Short-eared Owl and I shared a feeling some call heaven, some call pleasure, some call perfect. It is a feeling I live for, found so often at dusk. It is the feeling of life, and the Owl and I let the feeling pour upon us like warm water. As cars rushed by, I wondered why others would not stop to watch the sun fall. As mortal creatures, as any life is, it seems foolish to ignore such instances. I want to think that somewhere in the bird that watched the sun, there was a feeling of mortality and gratitude for the sun. Probably not so, but the bird served as a messenger to me the sentient, and drew my attention to the sun, the giver, the life provider for all.